Given that we are always going to store our data on a computer,

it makes sense for us to find out a little bit about

how that information is stored. How does a computer store the

letter `A' on a hard drive? What about the value ![]() ?

?

It is useful to know how to store information on a computer because this will allow us to reason about the amount of space that will be required to store a data set, which in turn will allow us to determine what software or hardware we will need to be able to work with a data set, and to decide upon an appropriate storage format. In order to access a data set correctly, it can also be useful to know how data has been stored; for example, there are many ways that a simple number could be stored. We will also look at some important limitations on how well information can be stored on a computer.

The surface of a CD

magnified many times to show the pits

in the surface that encode

information.7.2

The most fundamental unit of computer memory is the bit. A bit can be a tiny magnetic region on a hard disk, a tiny dent in the reflective material on a CD or DVD, or a tiny transistor on a memory stick. Whatever the physical implementation, the important thing to know about a bit is that, like a switch, it can only take one of two values: it is either “on” or “off”.

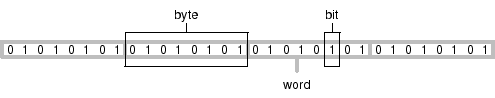

A collection of 8 bits is called a byte and (on the majority of computers today) a collection of 4 bytes, or 32 bits, is called a word. Each individual data value in a data set is usually stored using one or more bytes of memory, but at the lowest level, any data stored on a computer is just a large collection of bits. For example, the first 256 bits (32 bytes) of the electronic format of this book are shown below. At the lowest level, a data set is just a series of zeroes and ones like this.

00100101 01010000 01000100 01000110 00101101 00110001 00101110 00110100 00001010 00110101 00100000 00110000 00100000 01101111 01100010 01101010 00001010 00111100 00111100 00100000 00101111 01010011 00100000 00101111 01000111 01101111 01010100 01101111 00100000 00101111 01000100 00100000

The number of bytes and words used for an individual data value will vary depending on the storage format, the operating system, and even the computer hardware, but in many cases, a single letter or character of text takes up one byte and an integer, or whole number, takes up one word. A real or decimal number takes up one or two words depending on how it is stored.

For example, the text “hello” would take up 5 bytes of storage, one per character. The text “12345” would also require 5 bytes. The integer 12,345 would take up 4 bytes (1 word), as would the integers 1 and 12,345,678. The real number 123.45 would take up 4 or 8 bytes, as would the values 0.00012345 and 12345000.0.

A piece of computer memory can be represented by a series of 0's and 1's, with one digit for each bit of memory; the value 1 represents an “on” bit and a 0 represents an “off” bit. This notation is described as binary form. For example, below is a single byte of memory that contains the letter `A' (ASCII code 65; binary 1000001).

01000001

A single word of memory contains 32 bits, so it requires 32 digits to represent a word in binary form. A more convenient notation is octal, where each digit represents a value from 0 to 7. Each octal digit is the equivalent of 3 binary digits, so a byte of memory can be represented by 3 octal digits.

Binary values are pretty easy to spot, but octal values are much harder to distinguish from normal decimal values, so when writing octal values, it is common to precede the digits by a special character, such as a leading `0'.

As an example of octal form, the binary code for the character `A' splits into triplets of binary digits (from the right) like this: 01 000 001. So the octal digits are 101, commonly written 0101 to emphasize the fact that these are octal digits.

An even more efficient way to represent memory is hexadecimal form. Here, each digit represents a value between 0 and 16, with values greater than 9 replaced with the characters a to f. A single hexadecimal digit corresponds to 4 bits, so each byte of memory requires only 2 hexadecimal digits. As with octal, it is common to precede hexdecimal digits with a special character, e.g., 0x or #. The binary form for the character `A' splits into two quadruplets: 0100 0001. The hexadecimal digits are 41, commonly written 0x41 or #41.

Another standard practice is to write hexadecimal representations as pairs of digits, corresponding to a single byte, separated by spaces. For example, the memory storage for the text “just testing” (12 bytes) could be represented as follows:

6a 75 73 74 20 74 65 73 74 69 6e 67

When displaying a block of computer memory, another standard practice is to present three columns of information: the left column presents an offset, a number indicating which byte is shown first on the row; the middle column shows the actual memory contents, typically in hexadecimal form; and the right column shows an interpretation of the memory contents (either characters, or numeric values). For example, the test “just testing” is shown below complete with offset and character display columns.

0 : 6a 75 73 74 20 74 65 73 74 69 6e 67 | just testing

We will use this format for displaying raw blocks of memory throughout this section.

Recall that the most basic unit of memory, the bit, has two possible states, “on” or “off”. If we used one bit to store a number, we could use each different state to represent a different number. For example, a bit could be used to represent the numbers 0, when the bit is off, and 1, when the bit is on.

We will need to store numbers much larger than 1; to do that we need more bits.

If we use two bits together to store a number, each bit has two possible states, so there are four possible combined states: both bits off, first bit off and second bit on, first bit on and second bit off, or both bits on. Again using each state to represent a different number, we could store four numbers using two bits: 0, 1, 2, and 3.

The settings for a series of bits are typically written using a 0 for off and a 1 for on. For example, the four possible states for two bits are 00, 01, 10, 11. This representation is called binary notation.

In general, if we use k bits, each bit has two possible states, and the bits combined can represent 2k possible states, so with k bits, we could represent the numbers 0, 1, 2 up to 2k - 1.

Integers are commonly stored using a word of memory, which is 4 bytes or 32 bits, so integers from 0 up to 4,294,967,295 (232 - 1) can be stored. Below are the integers 1 to 5 stored as four-byte values (each row represents one integer).

0 : 00000001 00000000 00000000 00000000 | 1 4 : 00000010 00000000 00000000 00000000 | 2 8 : 00000011 00000000 00000000 00000000 | 3 12 : 00000100 00000000 00000000 00000000 | 4 16 : 00000101 00000000 00000000 00000000 | 5

This may look a little strange; within each byte (each block of eight bits), the bits are written from right to left like we are used to in normal decimal notation, but the bytes themselves are written left to right! It turns out that the computer does not mind which order the bytes are used (as long as we tell the computer what the order is) and most software uses this left to right order for bytes.7.3

Two problems should immediately be apparent: this does not allow for negative values, and very large integers, 232 or greater, cannot be stored in a word of memory.

In practice, the first problem is solved by sacrificing one bit

to indicate whether the number is positive or negative, so

the range becomes -2,147,483,647 to 2,147,483,647 (

![]() ).

).

The second problem, that we cannot store very large integers, is an inherent limit to storing information on a computer (in finite memory) and is worth remembering when working with very large values. Solutions include: using more memory to store integers, e.g., two words per integer, which uses up more memory, so is less memory-efficient; storing integers as real numbers, which can introduce inaccuracies (see below); or using arbitrary precision arithmetic, which uses as much memory per integer as is needed, but makes calculations with the values slower.

Depending on the computer language, it may also be possible to specify that only positive (unsigned) integers are required (i.e., reclaim the sign bit), in order to gain a greater upper limit. Conversely, if only very small integer values are needed, it may be possible to use a smaller number of bytes or even to work with only a couple of bits (less than a byte).

Real numbers (and rationals) are much harder to store digitally than integers.

Recall that k bits can represent 2k different states. For integers, the first state can represent 0, the second state can represent 1, the third state can represent 2, and so on. We can only go as high as the integer 2k - 1, but at least we know that we can account for all of the integers up to that point.

Unfortunately, we cannot do the same thing for reals. We could say that the first state represents 0, but what does the second state represent? 0.1? 0.01? 0.00000001? Suppose we chose 0.01, so the first state represents 0, the second state represents 0.01, the third state represents 0.02, and so on. We can now only go as high as 0.01 x (2k - 1), and we have missed all of the numbers between 0.01 and 0.02 (and all of the numbers between 0.02 and 0.03, and infinitely many others).

This is another important limitation of storing information on a

computer: there is a limit to the precision that we can

achieve when we store real numbers.

Most real values cannot be stored

exactly on a computer.

Examples of this problem include not only exotic values

such as transcendental numbers (e.g., ![]() and e), but also

very simple everyday values such as

and e), but also

very simple everyday values such as ![]() or even 0.1.

This is not as dreadful as it sounds,

because even if the exact value cannot be stored, a value

very very close to the true value can be stored. For

example, if we use eight bytes to store a real number

then we can store the distance of the earth from the sun to the

nearest millimetre.

So for practical

purposes this is usually not an issue.

or even 0.1.

This is not as dreadful as it sounds,

because even if the exact value cannot be stored, a value

very very close to the true value can be stored. For

example, if we use eight bytes to store a real number

then we can store the distance of the earth from the sun to the

nearest millimetre.

So for practical

purposes this is usually not an issue.

The limitation on numerical accuracy rarely has an effect on stored values because it is very hard to obtain a scientific measurement with this level of precision. However, when performing many calculations, even tiny errors in stored values can accumulate and result in significant problems. We will revisit this issue in Chapter 11. Solutions to storing real values with full precision include: using even more memory per value, especially in working, (e.g., 80 bits instead of 64) and using arbitrary-precision arithmetic.

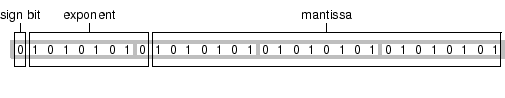

A real number is stored as a floating-point number, which means that it is stored as two values: a mantissa, m, and an exponent, e, in the form m x 2e. When a single word is used to store a real number, a typical arrangement7.4uses 8 bits for the exponent and 23 bits for the mantissa (plus 1 bit to indicate the sign of the number).

The exponent mostly dictates the range of possible values. Eleven bits allows for a range of integers from -127 to 127, which means that it is possible to store numbers as small as 10-39 (2-127) and as large as 1038 (2127).7.5

The mantissa dictates the precision with which values can be represented.

The issue here is not the magnitude of a value (whether it is very

large of very small), but the amount of precision

that can be represented.

With 23 bits, it is possible to represent 223 different real values,

which is a lot of values, but still leaves a lot of gaps. For example,

if we are dealing with values in the range 0 to 1, we can

take steps of

![]() ,

which means that we cannot

represent any of the values between 0.0000001 and 0.0000002.

In other words, we cannot distinguish between numbers that differ

from each other by less than 0.0000001.

If we deal with values in the range 0 to 10,000,000, we can only

take steps of

,

which means that we cannot

represent any of the values between 0.0000001 and 0.0000002.

In other words, we cannot distinguish between numbers that differ

from each other by less than 0.0000001.

If we deal with values in the range 0 to 10,000,000, we can only

take steps of

![]() ,

so we cannot distinguish between values that differ from each other by

less than 1.

,

so we cannot distinguish between values that differ from each other by

less than 1.

Below are the real values 1.0 to 5.0 stored as four-byte values (each row represents one real value). Remember that the bytes are ordered from left to right so the most important byte (containing the sign bit and most of the exponent) is the one on the right. The first bit of the byte second from the right is the last bit of the mantissa.

0 : 00000000 00000000 10000000 00111111 | 1 4 : 00000000 00000000 00000000 01000000 | 2 8 : 00000000 00000000 01000000 01000000 | 3 12 : 00000000 00000000 10000000 01000000 | 4 16 : 00000000 00000000 10100000 01000000 | 5

For example, the exponent for the first value is 0111111 1, which is 127. These exponents are “biased” by 127 so to get the final exponent we subtract 127 to get 0. The mantissa has an implicit value of 1 plus, for bit i, the value 2-i. In this case, the entire mantissa is zero, so the mantissa is just the (implicit) value 1. The final value is 20 x 1 = 1.

For the last value, the exponent is 1000000 1, which is 129, less 127 is 2. The mantissa is 01 followed by 49 zeroes, which represents a value of (implicit) 1 + 2-2 = 1.25. The final value is 22 x 1.25 = 5.

When real numbers are stored using two words instead of one, the range of possible values and the precision of stored values increases enormously, but there are still limits.

The central IT department of the University of Auckland has been collecting network traffic data since 1970. Measurements were made on each packet of information that passed through a certain location on the network. These measurements included the time at which the packet reached the network location and the size of the packet.

The time measurements are the time elapsed, in seconds,

since January ![]() 1970 and the measurements are extremely

accurate, being recorded to the nearest 10,000

1970 and the measurements are extremely

accurate, being recorded to the nearest 10,000![]() of a second.

Over time, this has resulted in numbers that are both very large

(there are 31,536,000 seconds in a year) and very precise.

Figure 7.2 shows several lines of the

data stored as plain text.

of a second.

Over time, this has resulted in numbers that are both very large

(there are 31,536,000 seconds in a year) and very precise.

Figure 7.2 shows several lines of the

data stored as plain text.

|

1156748010.47817 60 1156748010.47865 1254 1156748010.47878 1514 1156748010.4789 1494 1156748010.47892 114 1156748010.47891 1514 1156748010.47903 1394 1156748010.47903 1514 1156748010.47905 60 1156748010.47929 60 ... |

By the middle of 2007, the measurements were approaching the limits of precision for floating point values.

The data were analysed in a system that used 8 bytes per floating point number

(i.e., 64-bit floating-point values). The IEEE standard for 64-bit or

“double-precision” floating-point values uses 52 bits for the mantissa.

This allows for approximately7.6 252 different real values. In the range

0 to 1, this allows for values that differ by as little as

![]() , but when the numbers are

very large, for example on the order of 1,000,000,000, it is only

possible to store values that differ by

, but when the numbers are

very large, for example on the order of 1,000,000,000, it is only

possible to store values that differ by

![]() . In other words, double-precision floating-point

values can be stored with up to only 16 significant digits.

. In other words, double-precision floating-point

values can be stored with up to only 16 significant digits.

The time measurements for the network packets differ by as little as 0.00001 seconds. Put another way, the measurements have 15 significant digits, which means that it is possible to store them with full precision as 64-bit floating-point values, but only just.

Furthermore, with values so close to the limits of precision, arithmetic performed on these values can become inaccurate. This story is taken up again in Section 11.5.14.

Text is stored on a computer by first converting each character to an integer and then storing the integer. For example, to store the letter `A', we will actually store the number 65; `B' is 66, `C' is 67, and so on.

A letter is usually stored using a single byte (8 bits). Each letter is assigned an integer number and that number is stored. For example, the letter `A' is the number 65, which looks like this in binary format: 01000001. The text “hello” (104, 101, 108, 108, 111) would look like this: 01101000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111

The conversion of letters to numbers is called an encoding. The encoding used in the examples above is called ASCII7.7and is great for storing (American) English text. Other languages require other encodings in order to allow non-English characters, such as `ö'.

ASCII only uses 7 of the 8 bits in a byte, so a number of other encodings are just extensions of ASCII where any number of the form 0xxxxxxx matches the ASCII encoding and the numbers of the form 1xxxxxxx specify different characters for a specific set of languages. Some common encodings of this form are the ISO 8859 family of encodings, such as ISO-8859-1 or Latin-1 for West European languages, and ISO-8859-2 or Latin-2 for East European languages.

Even using all 8 bits of a byte, it is only possible to encode 256 (28) different characters. Several Asian and middle-Eastern countries have written languages that use several thousand different characters (e.g., Japanese Kanji ideographs). In order to store text in these languages, it is necessary to use a multi-byte encoding scheme where more than one byte is used to store each character.

UNICODE is an attempt to provide an encoding for all of the characters in all of the languages of the World. Every character has its own number, often written in the form U+xxxxxx. For example, the letter `A' is U+0000417.8and the letter `ö' is U+0000F6. UNICODE encodes for many thousands of characters, so requires more than one byte to store each character. On Windows, UNICODE text will typically use two bytes per character; on Linux, the number of bytes will vary depending on which characters are stored (if the text is only ASCII it will only take one byte per character).

For example, the text "just testing" is shown below saved via Microsoft's Notepad in three different encodings: ASCII, UNICODE, and UTF-8.

0 : 6a 75 73 74 20 74 65 73 74 69 6e 67 | just testing

The ASCII format contains exactly one byte per character. The fourth byte is binary code for the decimal value 116, which is the ASCII code for the letter `t'. We can see this byte pattern several more times, whereever there is a `t' in the text.

0 : ff fe 6a 00 75 00 73 00 74 00 20 00 | ..j.u.s.t. . 12 : 74 00 65 00 73 00 74 00 69 00 6e 00 | t.e.s.t.i.n. 24 : 67 00 | g.

The UNICODE format differs from the ASCII format in two ways. For every byte in the ASCII file, there are now two bytes, one containing the binary code we saw before followed by a byte containing all zeroes. There are also two additional bytes at the start. These are called a byte order mark (BOM) and indicate the order (endianness) of the two bytes that make up each letter in the text.

0 : ef bb bf 6a 75 73 74 20 74 65 73 74 | ...just test 12 : 69 6e 67 | ing

The UTF-8 format is mostly the same as the ASCII format; each letter has only one byte, with the same binary code as before because these are all common english letters. The difference is that there are three bytes at the start to act as a BOM.7.9

When storing values with a known range, it can be useful to take advantage of that knowledge. For example, suppose we want to store information on gender. There are (usually) only two possible values: male and female. One way to store this information would be as text: “male” and “female”. However, that approach would take up at least 4 to 6 bytes per observation. We could do better by storing the information as an integer, with 1 representing male and 2 representing female, thereby only using as little as one byte per observation. We could do even better by using just a single bit per observation, with “on” representing male and “off” representing female.

On the other hand, storing “male” is much less likely to lead to confusion than storing 1 or by setting a bit to “on”; it is much easier to remember or intuit that “male” corresponds to male. This leads us to an ideal solution where only a number is stored, but the encoding relating “male” to 1 is also stored.

Dates are commonly stored as either text, such as Feb 1 2006, or as a number, for example, the number of days since 1970. A number of complications arise due to a variety of factors:

There are two major issues with storing monetary values. The first is that the currency should be recorded; NZ$1.00 is very different from US$1.00. This issue applies of course to any value with a unit, such as temperature, weight, distances, etc.

The second issue with storing monetary values is that values need to be recorded exactly. Typically, we want to keep values to exactly two decimal places at all times. This is sometimes solved by using fixed-point representations of numbers rather than floating-point; the problems of lack of precision do not disappear, but they become predictable so that they can be dealt with in a rational fashion (e.g., rounding schemes).

In the standard examples we have seen so far (text and numbers), a single letter or number has been stored in one or more bytes. These are good general solutions; for example, if we want to store a number, but we do not know how big or small the number is going to be, then the standard storage methods will allow us to store pretty much whatever number turns up. Another way to put it is that if we use standard storage formats then we do not have to think too hard.

It is also true that computers are designed and optimised, right down to the hardware, for these standard formats, so it usually makes sense to stick with the mainstream solution. In other words, if we use standard storage formats then we do not have to work too hard.

All values stored electronically can be described as binary values because everything is ultimately stored using one or more bits; the value can be written as a series of 0's and 1's. However, we will distinguish between the very standard storage formats that we have seen so far, and less common formats which make use of a computer byte in more unusual ways, or even use only fractional parts of a byte.

An example of a binary format is a common solution that is used for storing colour information. Colours are often specified as a triplet of red, green, and blue intensities. For example, the colour (bright) “red” is as much red as possible, no green, and no blue. We could represent the amount of each colour as a number, say, from 0 to 1, which would mean that a single colour value would require at least 3 words (12 bytes) of storage.

A much more efficient way to store a colour value is to use just a single byte for each intensity. This allows 256 (28) different levels of red, 256 levels of blue, and 256 levels of green, for an overall total of more than 16 million different colour specifications. Given the limitations on the human visual system's ability to distinguish between colours, this is more than enough different colours.7.10Rather than using 3 bytes per colour, often an entire word (4 bytes) is used, with the extra byte available to encode a level of translucency for the colour. So the colour “red” (as much red as possible, no green and no blue) could be represented like this:

00 ff 00 00

00000000 11111111 00000000 00000000

Paul Murrell

This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License.